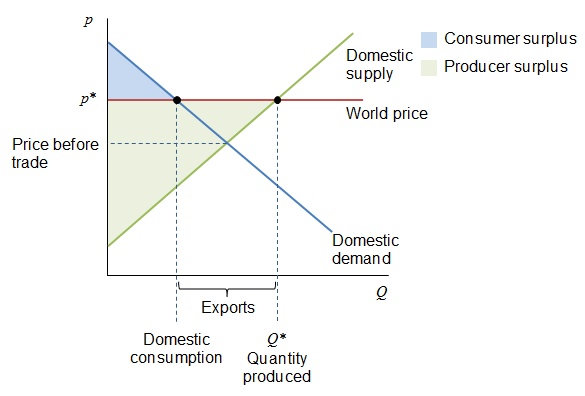

Here’s a little refresher on the microeconomic view of international trade. For simplicity, we assume perfectly competitive domestic and international markets. That means domestic consumers can buy as much foreign goods as they want without affecting the world price. Similarly, domestic producers can sell as much as they want in foreign markets without affecting the world price. While not essential to the basic results, these assumptions make the graphs easier to interpret (and draw!).

First, let’s establish the baseline: no trade. The graph below shows the market for some product in a closed economy. Supply and demand refresher: price is on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal. The demand curve shows the relationship between price and the quantity consumers will buy (with other factors held constant). That is, the demand curve shows how much people are “willing and able” to pay for the product at each price. It’s downward sloping because of the law of demand: the more things cost, the less people are willing to buy it.

The supply curve shows how much producers are will to sell at various prices. It is upward sloping because marginal costs increase in the short-run (fixed assets) as output increases. The place where supply and demand intersect is the market equilibrium. The price, p*, is the “market clearing price” because, at that price, consumers are willing and able to buy exactly the amount suppliers make available.

In a competitive market, this equilibrium maximizes total social benefit, as measured by the sum of consumer and producer surpluses. Each surplus is simply a measure of the gains from each individual transaction. For example, the difference between what a consumer is willing to pay (i.e., demand) and what he actually pays (i.e., price). Note that while this result is efficient (makes the largest total social benefit), there are still people who are unhappy with the arrangement. There are consumers who are not willing (or able) to purchase the good at price p*. Similarly, there are sellers whose costs are too high to stay in business when prices are at p*.

Now, if we make this an open economy, and the domestic suppliers have a comparative advantage over foreign suppliers (i.e., produce at lower opportunity cost), the world price will exceed the domestic price, as shown below. In this case, those unhappy producers in the closed economy might be able to sell their wares at the higher global price. The catch is, producers will divert production to satisfy world demand at the higher price, and domestic consumers are hurt. They end up consuming less product at a higher price. However, the total amount of surplus increases overall.

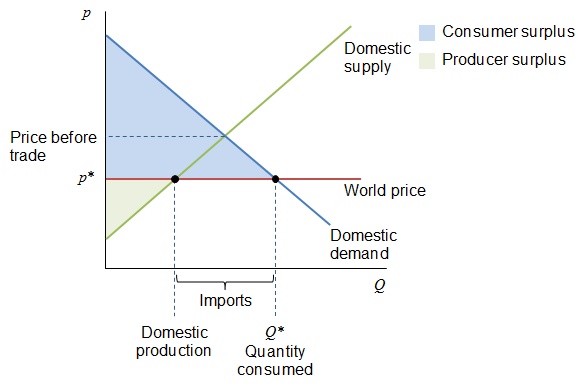

Suppose instead that the world price is lower than the domestic price was in the closed economy. In this case, consumers are better off because they can consume more of the product and at a lower price. The domestic producers, however, have to compete at that lower price, so some of them will not be able to survive. In this scenario, the consumers benefit at the expense of producers, but as before, the total amount of surplus increases compared to the closed economy.

The difference between these two scenarios is the allocation of the “pain.” In the first case (exports), the affected consumers are very numerous, and their individual expense is probably negligible (a slightly higher price paid by each of them). The producers, however, are smaller in number, so the gains are more concentrated. Similarly, in the import scenario, there are many consumers whose individual benefit is only a slightly lower price. The producers, being fewer in number, feel a bigger impact from competition. (Imagine closing a factory versus saving a couple dollars at the store.) The producers have more incentive to lobby the government for assistance in both scenarios. That basically explains why governments frequently subsidize their exporters and impose trade barriers to protect their importers. These barriers include tariffs (taxes) and quotas (limits on the amount of imports). Let’s look at a tariff.

The graph below shows the same import market with a tariff added. Since the tariff is simply a tax per unit, the after-tax world supply curve effectively moves up by the amount of the tariff. The result is an increase in output for domestic producers and a decrease in consumption by consumers, who also pay a higher price. The government also benefits from the tax revenue collected. Notice the total surplus in this scenario is reduced. This frequently occurs whenever government policies interfere in an efficient market. The loss of surplus is called “dead weight loss.” It’s like trying to transfer water with a bucket; some of it always splashes out and is wasted.

There are many arguments producers (and politicians) use to justify trade protections. These include domestic jobs, infant industry protection, national security, and unfair competition by foreign companies. Regardless of the reason, the actual impact of protection exceeds our simple analysis because each country does not act in isolation. Once a nation imposes trade protections, the other nations impose their own protections in retaliation. The benefits a government seeks for its domestic industries, therefore, will hurt its export industries as well as its consumers. More importantly, these protections interfere in the free market’s ability to use prices as signals to guide the efficient allocation of resources.

If you want more information without getting into differential equations, pick up any introductory macroeconomics textbook. I’ve taught with N. Gregory Mankiw’s Essentials of Economics, Robert Frank and Ben Bernanke’s Principles of Economics, and Thomas Sowell’s Basic Economics. Mankiw does the best job of covering trade.